The next morning, those of us who can keep any food down are queuing along the upper deck, waiting our turn to descend to the mess deck for breakfast. Here we learn that one of our three engines is useless, and that one of the screws has broken during the pitching and tossing of the night.

After breakfast I go up on deck again and see to the starboard a mountainous island rearing itself from the sea, an island encircled by cloud, gloomy and menacing. Corsica! The island of Prosper Mérimée and of Guy de Maupassant who wrote such bloodthirsty tales about Corsican vendettas; the home of that military and administrative genius and scourge of Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte; and of that “other Corsican”, the singer Tino Rossi. No doubt Corsica is a beautiful island, but today, looming and misty, it has an air of menace.

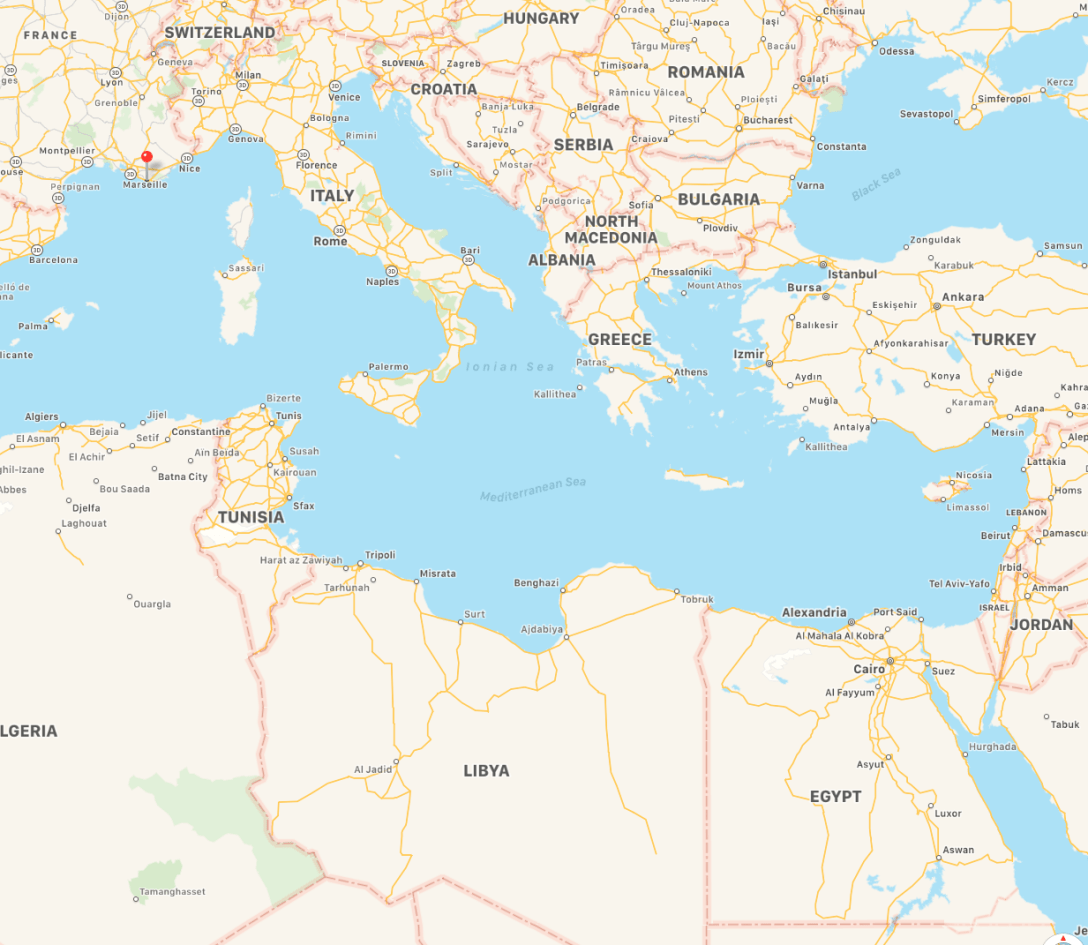

Towards midday the sea began to get extremely rough again, and become more or less calm only at twilight on the third day, when we were sailing between the green, hilly coast of Italy and the island of Sicily. Here, in nineteen forty-three, the allies had successfully completed the invasion of Sicily from North Africa. Then they and the Germans gazed at each other from opposite sides of the narrow Straits of Messina, poised ready to spring at each other’s throats.

Some members of the ship’s crew told us that this was the roughest crossing of the “Med” they had ever known, and we could quite believe them. Nevertheless, we had periods of relative calm. At these times, it was good to promenade the deck and look at the immense expanse of sea, really blue now, whose billowing, white-crowned waves leapt and pranced as far as the eye could reach. Sometimes, when the sun shone and the skies were swept clear of clouds, it was most pleasant to lean on the handrail and look at the turbulent, foaming water cut and flung aside without mercy by the bow of our ship. I shall always remember one night when I had climbed on deck to get a breath of fresh air. It was pitch black. The sea and the sky were fused together in one single mass of darkness. Only the beat of water against the iron body of the ship could be heard. A few squares of light, escaping from the cabin windows illuminated, from time to time, foaming whirlpools, or white, threatening waves. Then, from the other end of the deck, men began to sing. Others joined in. And suddenly it was a wonderful blend of deep, melodious, all-male voices, and of the hissing passage of beaten, foaming sea. Everything was in rhythm. The soft wind carried away my cares, and nothing mattered in the world except the beauty of that moment.

At about ten o’clock in the evening of the sixth day, we saw to starboard twinkling points of light. Over there lies the coast of Egypt, and we are approaching Port Said. The acolytes of the engine room have had their work cut out on this voyage. They have worked frenziedly, but rumour has it that despite their efforts two of our three engines have failed, and we have sprung leaks in three places. Certainly we are visibly lower in the water, but all’s well that ends well. In half an hour we are at Port Said, the motors stop, and we drift with the calm, black waters shimmering and sucking at the sides of our ship. Opposite, on shore, are myriad lamps throwing a wan light on deserted streets. They illuminate monstrous cranes and send a thousand reflections jumping and glittering across the rippling water.

Sirens sound. Busy little bum-boats approach us. I see for the first time an Egyptian wrapped in a garment like an outsize white nightshirt, which I later learn is called a galabieh, with a red fez on his head. But the illusion of a dignified, mysterious oriental world is shattered when an Arab vendor, who has failed to sell a soldier a leather handbag, gives vent to his disappointment in very colloquial Anglo-Saxon English, making me believe that his command of ‘four-letter words’ is possibly equal to my own. Ah, well, it just goes to prove that English really is the true international language.

Although it is night, the wind on my cheeks from the neighbouring desert is warm. When are we to disembark? Nobody knows. In the British army you get used to waiting for somebody else to make decisions for you. However, this is my first journey outside Europe. I’m in no hurry, and it is pleasant to watch the Arab vendors who have gained access to the deck, and a conjuror who gives a ten-minute floor show for suitable remuneration and produces small day-old chicks from the most unlikely places.

Eventually we disembark at two o’clock in the morning. Our large valises are strapped to our backs; our small valises are on our hips. For portability we wear our thick great coats under our webbing. We hump our heavily laden kit bags on our shoulders. Sweating and cursing we cut across the quay, file between shadowy bales stacked one on top of the other, and scramble aboard an Egyptian train waiting in a siding.

During this time a few very young soldiers, who haven’t kept up with our group, lose themselves after leaving the “Empire Battleaxe”, get tangled up with a completely different group of soldiers who are leaving Egypt, and finish up in another ship. This sails triumphantly into the wide blue yonder carrying our friends back to dear old Blighty! We hear nothing of them until several weeks later. Having sailed the length of the Mediterranean three times, they finally finish up at our camp in Egypt, where they should have arrived the first time. That’s par for the course with the British army – everything in a state of absolute and continuous chaos! God only knows what the pay clerks costed their wages to!

Fortunately my own small party reached its allotted railway carriage with no difficulty. I fell asleep on a wooden bench in the long, grey coach in which I found myself after having unhooked my corset of webbing and let everything fall to the floor.

When I awoke, dawn had broken, we were rattling along at a fine speed, and it was surprisingly cold for a tropical country. It was February and still mid winter. Through the windows we could see the yellow, undulating desert. But there were wide lengths of greenery close to the railway, and tall, soaring palm trees dotted the adjoining landscape. Often we passed tumbledown, seemingly half-completed dwellings, on whose roofs were untidy piles of straw, apparently placed as protection against the heat of the sun.

At this hour Arabs were leaving their hovels like animals quitting their caves. Men enveloped in white, burnous-like galabiehs and muffled to the eyes because of the cold, travelled astride small, trotting donkeys. Each was followed by his wife – on foot! – swaddled in a black shawl and generally veiled. Sometimes, the donkey was replaced by a slow, ugly, incessantly nodding camel. One could not fail to notice the abject poverty of these “fellahin”, and this never ceased to appall us during the whole of our stay in Egypt. There seemed to be the very poor and the very rich, with only a small and insignificant middle class.

Towards ten o’clock in the morning it got very hot. Off came greatcoats, and tunics were unbuttoned. The country became bare, dry and uninviting. The trains stopped at several stations, and hordes of vendors descended on us. The technique was for them to approach us slyly and to show suddenly a glittering ring, which they would immediately hide again in a dirty palm. How much? – Two pounds, effendi. A real bargain, oombashi. After the usual haggling, of course, these prices would descend spectacularly to something in the region of five piastres – a shilling.

Then sellers of oranges, (stolen from roadside groves), would do their best to make a quick turn at our expense. Or banana sellers would clamber aboard, and there was a temptation, for bananas had not been available in England for years. Unfortunately or otherwise we had received no Egyptian money as yet, and very few of our lads had any English or French money left. One thing that surprised us was the fluency with which these dirty, apparently uneducated natives spoke English. Doubtless their range was narrow, but within that range their fluency was perfect. They had, of course, learnt the language by ear, and their grammar was more often than not at fault, but here was a demonstration if I ever saw one of the necessity for linguistic back-up in foreign language teaching, and of the poverty of book teaching if that linguistic back-up is omitted.

At about one o’clock in the afternoon, the train pulled into a siding and we got out. We clambered into lorries, passed through the outskirts of Cairo, and arrived at a reception camp on the edge of the suburb of Heliopolis. The Greek name was well given, for the sun beat down from a cloudless sky and glared back from the white walls of the stone buildings. The lorries stopped, vomited men with their heavy kit and clattering hob-nailed boots, then moved off as each soldier set about finding an empty space in the sea of white tents which covered a plain of sand.

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/maps/africa/zoomify136595.html

[Above is an interactive map from The British Library Online, showing an array of allied sites in Cairo in 1946, and where the troops may or may not go.]

We stayed at this camp for three weeks. There was little to do except scrub one’s packs and webbing with sand and water until they were white. An Arab would be only too pleased to perform this enervating task for a couple of piastres. We used to spend the evenings on the canteen terrace, drinking tea from glasses made from beer bottles, chatting and writing letters.

At this time the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty governing the British occupation was up for rediscussion. There was much talk about this in the newspapers. The better class of Egyptian – the effendim – did not seem particularly anglophobe. No doubt they realised which side their bread was buttered and understood the vast amounts of British currency keeping the economy afloat. But a few louts from among the fellahin used to wait for us in the guise of boot blacks at the entrance to the camp. Thus, whenever we were going into Heliopolis or Cairo we had to run the gauntlet of these fellows, who would approach us pretending to want to clean our shoes. These were always dirty after we had trudged across the sand to the gates. To accept, however, meant that one’s trousers would be smothered in boot polish. We were officially forbidden to resist these people, however much they pestered us, thus cracking a few heads with some sticks and putting an end to the matter was out of the question. However, we used to go out in groups, and if a bunch of Arabs became threatening, there were always a few large stones around which we could pick up and look as if we were prepared to use – as indeed we were. Thus a number of ugly incidents, which blew up from time to time, always seemed to peter out.

The native shops and stalls, the bistros with their tables scattered across the pavement at which Arabs – some dressed in galabiehs, some European fashion, but most wearing the ubiquitous fez – sat drinking coffee and often smoking hookahs, had a great interest for us. This was unfortunately marred by the hostility we encountered during our first days in Egypt.

Another pastime of the Arabs in the vicinity was to organise raids on the camp. At night, they would cut the barbed wire which marked the perimeter, quietly enter the tents, and steal whatever they could lay their hands on. A rifle was worth twenty Egyptian pounds, a small fortune for a fellah, which was one of the reasons why the arms of all British forces in the Middle East were kept in locked armouries when their owners did not need them.

From Lynda

Jim is on an adventure that not even the “the turbulent, foaming water cut and flung aside without mercy by the bow of our ship” can dampen. I breathe a huge sigh of release as I read: “The soft wind carried away my cares, and nothing mattered in the world except the beauty of that moment.”

There are so many wonderful descriptions, that the contrast is palpable on arrival in Cairo. Jim is aware of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, but I do not believe that these young men were aware of the underlying tensions and politics, in to which they were walking. Once again, the ordinary soldier was “forbidden to resist these people”. It is only an order, the education or explanation seems to be lacking. And we already know what Jim thinks about orders without being informed.

LikeLike

From Trish

This chapter’s beginning sounds like a Boys Own adventure. The swash-buckling Bonaparte, tales of Corsican adventures, a rough, leaking boat trip across the Mediterranean to Egypt, and men in spontaneous song expressing their harmony with the moment and nature, are a suitable trade for these soldiers from the previous sounds of war.

Jim listens to and visualises the sounds of Egypt as an exotic country, rich in difference to “Blighty”. However the echelons of the class system seem to have no boundaries where ever power and money are superior to equality.

In this chapter I am reminded of the influence and outcomes of British occupation on foreign soil, and their long term effects changing the history and uniqueness of those countries, including Egypt.

LikeLike